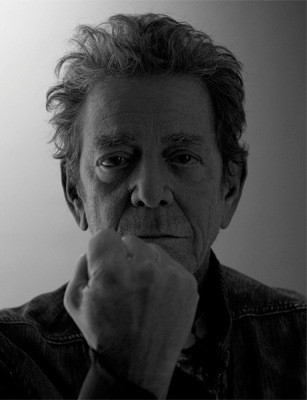

Junior Murvin, the Jamaican singer with the distinctive falsetto, whose hit “Police and Thieves” became well known in the punk community when The Clash covered it on their 1977 debut album, died at Port Antonio Hospital in Jamaica today, according to his son Keith Smith. Various reports have put his age at either 64 or 67.

Murvin had been hospitalized recently for diabetes and high blood pressure but the cause of death has yet to be determined.

According to The Independent, “Police and Thieves” was recorded in 1976 to reflect turf war and police violence in Jamaica but became closely associated with London’s Notting Hill Carnival, which ended in rioting that year.” The song eventually became a British hit For Marvin in 1980.

Murvin never again achieved the success of “Police and Thieves,” which was produced by the legendary Lee “Scratch” Perry at Perry’s Black Ark studio in Washington Gardens, St Andrew.

Reggae-vibes.com has this about “Police and Thieves”: “He [Junior Murvin] had met Perry years before when Scratch auditioned singers who wanted to record at Coxsone Dodd’s Studio One. Scratch introduced Junior Murvin to Coxsone Dodd as a singer with potential. Coxsone heard the song and told Junior to learn another verse to his song. Junior never returned and never recorded at Studio One. “I never had the patience to wait at that point”. He had come to Kingston to look for a producer for his song and this is how it happened: “It was a vibes y’know – of the producers at that time, only he could manage that heavy hardcore – cause I just get a vision to go to him and that was it. Lee Perry is the greatest producer I ever work with”. Together he and Scratch developed “Police And Thieves” and by its popularity was to prove the cry of the Jamaican people in the strife torn mid-seventies and early eighties. “He (Perry) always said to me ‘bwoy with the tune that you make you nah go dead’. True I was young I never realise what him a tell me – true he was older than me – but now me start get bigger me understand”. Junior and Scratch developed a relationship where they counteracted each other: “Me give Lee Perry nuff idea too y’know nuff idea. Him like work with me too… we have same idea, some time me have the idea before him – him say ‘When you have it ?’. He is a man who when you have voicing – him can talk through the mic and tell you three bars before the bridge comes – he just phrase in your ears – remind you say ‘Junior phrase away now remember the bar a come, phrase away now the bar a come now-hit it!’. (Laughs) When you’re voicing he’s talking through the mic in your ears – coming down with the music y’know and dancing too – give you a vibes. …..Him a dance and a mix, people who play instrument them always dance, but he’s the only man who I see mix and dance….”

The Clash’s version:

— A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post —