In response to my post yesterday, “Bob Dylan’s ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ Manuscript Sells for $2 Million But Dylan’s Secrets Remain Secret,” Mike Jones commented:

The LARS lyrics went for more than I thought they would…how are a few pieces of paper worth more than the Newport guitar? I don’t get the whole ephemera thing. I guess people like to have historical stuff, just to look at or whatever. But I would much rather have the Newport guitar, which sold for like half as much. That seems very strange to me.

I understand why some folks, especially musicians, would want the guitar Bob Dylan played at the Newport Folk Festival gig that drew the line between the old Dylan, and the new.

For me though — and I’m not saying paying $2 mil makes any kind of sense — between the guitar and the manuscript, I’d go for the manuscript.

Guitar:

Here’s why.

Certainly the guitar is an iconic object, symbolic of Dylan’s rejection of so-called ‘folk music’ for rock ‘n’ roll, but he could have played any Strat that day and made the same music, made the same impact. Dylan’s art and his creativity didn’t hinge on that particular guitar. In fact, he played many guitars over the years. It’s always been Dylan, not his instruments, that makes the difference.

But that manuscript.

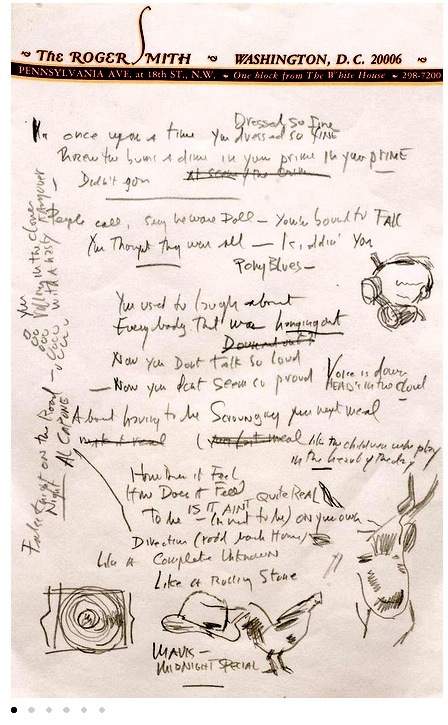

That’s the artist at work. That’s the artist in the throes of the creative process.

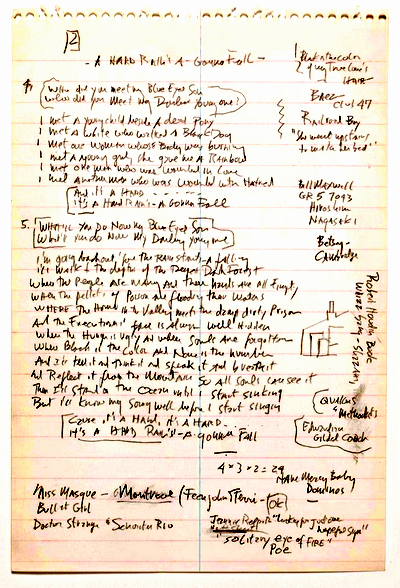

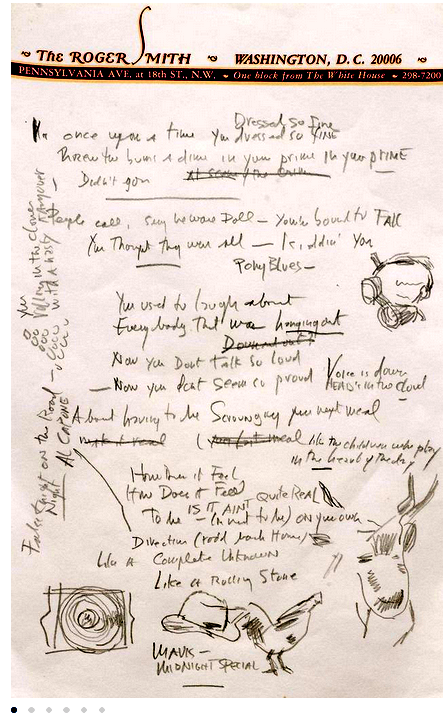

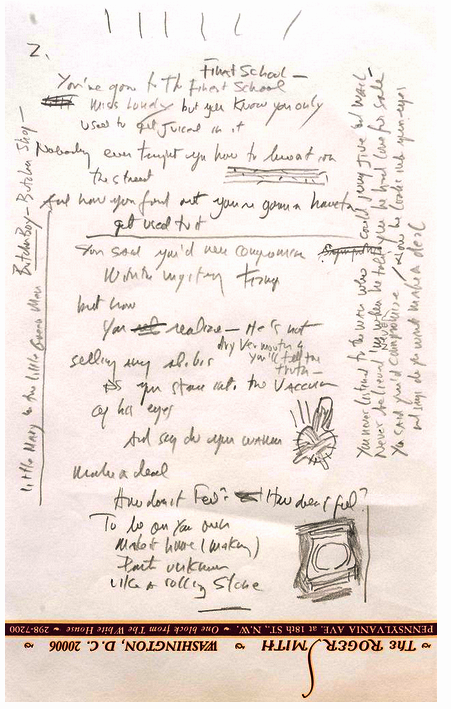

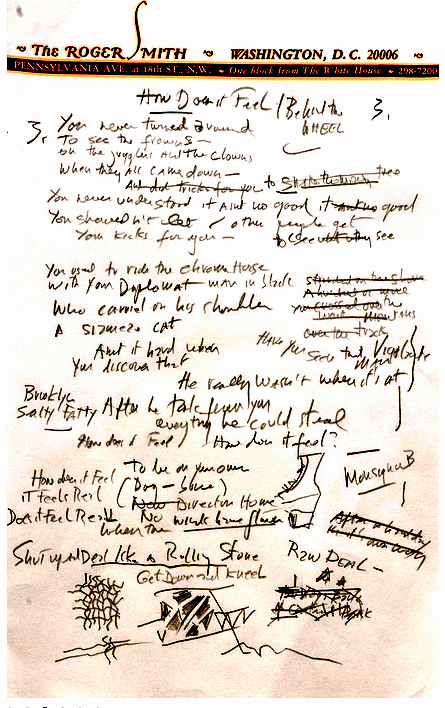

On those pages we see the song take shape. Words crossed out and other words written in. The chorus forming before our eyes from page to page.

And those cryptic notes to the side of the lyrics. “Al Capone,” “On the Road,” “Pony Blues,” “Butcher Boy.”

From these pages and the ones for “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” we get the curtain pulled back a little on Dylan’s creative process.

And when one combines what’s on these pages, with what he reveals in “Chronicles: Volume One” and elsewhere, we do get a vague sense of the Dylan mind at work.

We’ll never get to the bottom of it, and it’s probably better that way, but still.

So Bob Dylan’s ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ lyrics are very different from the Newport guitar. They’re a time machine that takes us back to that day (s) when Bob Dylan put the ideas that were in his head down on hotel stationary, and created a timeless song, a song that, nearly 50 years after he wrote it, stands tall.

But what do you think?

Would you opt for the Newport guitar, or the “Like A Rolling Stone” manuscript pages?

Manuscript:

Or is there something else that you’d go for instead. If you had the money, and if you could afford to spend it in this way.

Bob Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 singing “Like A Rolling Stone”:

Bob Dylan – Like a Rolling Stone (Live… by toma-uno

— A Days Of The Crazy-Wild blot post —