A few weeks back I put together a post called “Ten Films That Had a Big Impact On Bob Dylan.”

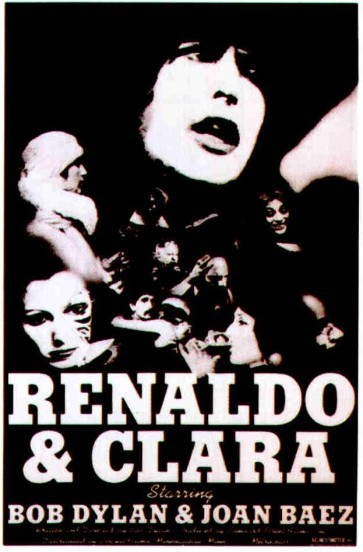

One of the people who read that post, Will Dockery, commented on that post and included a short quote from a Rolling Stone interview that Jonathan Cott did with Dylan that was published January 26, 1978 (the day after “Renaldo & Clara” was first shown in movie theaters in New York and Los Angeles).

I found the interview and have included some of it below.

While Dylan is specifically talking about what influenced his filmmaking, clearly film has influenced him as an artist in many ways.

I’ve excerpted a section where he talks about other directors and mentions a few films. You can find the interview in a book edited by Jonathan Cott called “Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews” published by Wenner Books. It’s also online here (but it’s possible you have to be a Rolling Stone subscriber to get access — I’m not sure).

The movie that creates the context for this conversation is, of course, “Renaldo & Clara.”

Bob Dylan: I know this film is too long. It may be four hours too long — I don’t care. To me, it’s not long enough. I’m not concerned how long something is. I want to see a set shot. I feel a set shot. I don’t feel all this motion and boom-boom. We can fast cut when we want, but the power comes in the ability to have faith that it is a meaningful shot.

You know who understood this? Andy Warhol. Warhol did a lot for American cinema. He was before his time. But Warhol and Hitchcock and Peckinpah and Tod Browning . . . they were important to me. I figured Godard had the accessibility to make what he made, he broke new ground. I never saw any film like Breathless, but once you saw it, you said: “Yeah, man, why didn’t I do that, I could have done that.” Okay, he did it, but he couldn’t have done it in America.

Trailer for “Breathless”:

“Breathless” (Dutch subtitles):

Excerpt from Tod Browning’s “Freaks”:

Andy Warhol’s “Beauty Number 2”:

Jonathan Cott: But what about a film like Sam Fuller’s Forty Guns or Joseph Lewis’ Guns Crazy?

Yeah, I just heard Fuller’s name the other day. I think American filmmakers are the best. But I also like Kurosawa, and my favorite director is [Luis] Buñuel; it doesn’t surprise me that he’d say those amazing things you quoted to me before from the New Yorker.

Buñuel’s “El Angel Exterminador”:

[Earlier in the interview Cott read a Buñuel quote to Dylan from a New Yorker interview: “Mystery is an essential element in any work of art. It’s usually lacking in film, which should be the most mysterious of all. Most filmmakers are careful not to perturb us by opening the windows of the screen onto their world of poetry. Cinema is a marvelous weapon when it is handled by a free spirit. Of all the means of expression, it is the one that is most like the human imagination. What’s the good of it if it apes everything conformist and sentimental in us? It’s a curious thing that film can create such moments of compressed ritual. The raising of the everyday to the dramatic.”]

I don’t know what to tell you. In one way I don’t consider myself a filmmaker at all. In another way I do. To me, Renaldo and Clara is my first real film. I don’t know who will like it. I made it for a specific bunch of people and myself, and that’s all. That’s how I wrote “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “The Times They Are A-Changin'” — they were written for a certain crowd of people and for certain artists, too. Who knew they were going to be big song

The film, in a way, is a culmination of a lot of your ideas and obsessions.

That may be true, but I hope it also has meaning for other people who aren’t that familiar with my songs, and that other people can see themselves in it, because I don’t feel so isolated from what’s going on. There are a lot of people who’ll look at the film without knowing who anybody is in it. And they’ll see it more purely.

Eisenstein talked of montage in terms of attraction — shots attracting other shots — then in terms of shock, and finally in terms of fusion and synthesis, and of overtones. You seem to be really aware of the overtones in your film, do you know what I mean?

I sure do.

Eisenstein once wrote: “The Moscow Art is my deadly enemy. It is the exact antithesis of all I am trying to do. They string their emotions together to give a continuous illusion of reality. I take photographs of reality and then cut them up so as to produce emotions.”

Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin”:

What we did [in Renaldo & Clara”] was to cut up reality and make it more real . . . Everyone from the cameramen to the water boy, from the wardrobe people to the sound people was just as important as anyone else in the making of the film. There weren’t any roles that well defined. The money was coming in the front door and going out the back door: The Rolling Thunder tour sponsored the movie. And I had faith and trust in the people who helped me do the film, and they had faith and trust in me.

In the movie, there’s a man behind a luncheonette counter who talks a lot about truth — he’s almost like the Greek chorus of the film.

Yeah, we often sat around and talked about that guy. He is the chorus.

That guy at one point talks about the Movement going astray and about how everyone got bought off. How come you didn’t sell out and just make a commercial film?

I don’t have any cinematic vision to sell out. It’s all for me so I can’t sell out. I’m not working for anybody. What was there to sell out?

Well, movies like “Welcome to L.A.” and “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” are moralistic exploitation films — and many people nowadays think that they’re significant statements. You could have sold out to the vision of the times.

Right. I have my point of view and my vision, and nothing tampers with it because it’s all that I’ve got. I don’t have anything to sell out.

Renaldo and Clara has certain similarities to the recent films of Jacques Rivette. Do you know his work?

I don’t. But I wish they’d do it in this country. I’d feel a lot safer. I mean I wouldn’t get so much resistance and hostility. I can’t believe that people think that four hours is too long for a film. As if people had so much to do. You can see an hour movie that seems like 10 hours. I think the vision is strong enough to cut through all of that. But we may be kicked right out of Hollywood after this film is released and have to go to Bolivia. In India, they show 12-hour movies. Americans are spoiled, they expect art to be like wallpaper with no effort, just to be there.

Jacques Rivette’s “Paris Nous Appartient”:

-– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –-