Three songs from Bob Dylan’s performance at Durham Performing Arts Center, Durham, NC, on April 25, 2015.

“Things Have Changed”:

“Blowin’ In The Wind”:

“Stay With Me”:

– A Days Of The Crazy-Wild blog post –

Three songs from Bob Dylan’s performance at Durham Performing Arts Center, Durham, NC, on April 25, 2015.

“Things Have Changed”:

“Blowin’ In The Wind”:

“Stay With Me”:

– A Days Of The Crazy-Wild blog post –

In 1954 Webb Pierce’s “More and More” spent ten weeks atop the country charts (and reached #22 on the pop charts).

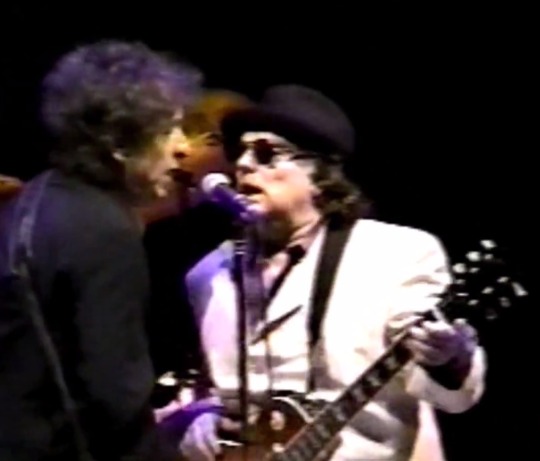

Check out this cool version by Bob Dylan and Van Morrison, which is from a January 16, 1998 concert in New York at The Theater, Madison Square Garden.

Dylan joined Morrison during Morrison’s set.

Here’s Webb Pierce singing “More and More”:

Plus here’s Dylan and Morrison singing “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”:

– A Days Of The Crazy-Wild blog post –

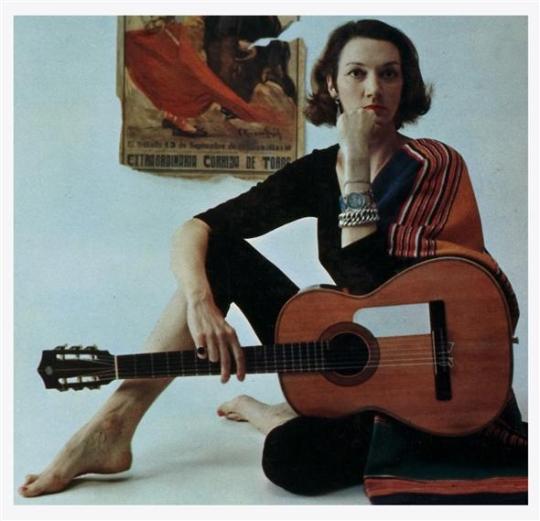

Beginning in 1975, Bob Dylan and a superstar troupe of folk and rock musicians hit the road as the Rolling Thunder Review. As the tour progressed a camera crew filmed some of the concerts as well as fictional scenarios that Dylan dreamed up, and real off-stage events.

One of my favorite performances from the tour (included in “Renaldo & Clara”) is the Dylan and Joan Baez version of Johnny Ace’s 1954 R&B hit, “Never Let Me Go” (written by Joseph Scott).

Video clip from “Renaldo & Clara”:

Full song:

“Never Let Me Go”:

Another version from the Rolling Thunder Review tour:

And another:

Johnny Ace’s version:

— A Days of The Crazy-Wild blog post —

The MusicCares Bob Dylan tribute concert from earlier this year which honored Dylan as 2015 MusiCares Person of the Year will be released on DVD, according to Billboard magazine.

The concert, which took place on Friday February 6, 2015, included performances by Bruce Springsteen, Jack White, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Norah Jones, Tom Jones, Los Lobos, John Mellencamp, Alanis Morissette, Willie Nelson, Aaron Neville, Sheryl Crow, Bonnie Raitt, Derek Trucks, John Doe, Jackson Browne and Neil Young. It is expected that they will all appear on the DVD.

As of now, it’s not known if Dylan’s 35-minute MusicCares speech will be on the DVD. In an earlier version of this post I reported that it would be included but that was an error. For now there is no info about the speech being included.

Dylan personally chose the performers and the songs they would sing at the MusicCares event.

Here are the songs performed:

Beck – “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat”

Aaron Neville – “Shooting Star”

Alanis Morissette – “Subterranean Homesick Blues”

Los Lobo – “On A Night Like This”

Willie Nelson – “Señor (Tales Of Yankee Power)”

Jackson Browne – “Blind Willie McTell”

John Mellencamp – “Highway 61 Revisited”

Jack White – “One More Cup Of Coffee”

Tom Jones – “What Good Am I?”

Norah Jones – “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”

Dereck Trucks And Susan Tedeschi – “Million Miles”

John Doe – “Pressing On”

Crosby, Stills & Nash – “Girl From The North County”

Bonnie Raitt – “Standing In The Doorway”

Sheryl Crow – “Boots Of Spanish Leather”

Bruce Springsteen – “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”

Neil Young – “Blowin’ In The Wind”

Hear excerpts:

The DVD release date has yet to be announced.

You can read the Billboard story here.

Meanwhile you can read the Dylan speech here.

— A Days Of The Crazy-Wild blog post —

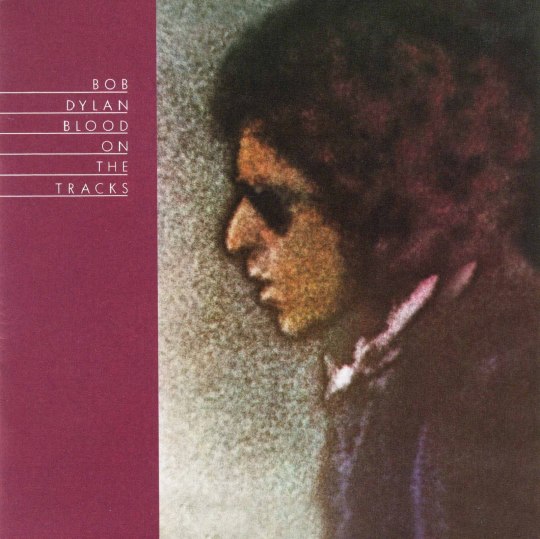

Forty years ago, just after rock critic Jon Landau became Bruce Springsteen’s manager and record producer, his review of Bob Dylan’s Blood On The Tracks appeared in the March 13, 1975 issue of Rolling Stone.

What is most interesting to me about the review, some of which is printed below and the rest of it you can link to, is how, what complains about in critiquing Dylan’s recording style and records — that Dylan makes records too quickly, that he doesn’t use the right musicians, and so on — are the things he made sure Bruce Springsteen didn’t do. What I mean is, Dylan might record an album in a few days and record just two or three takes of a song; Springsteen sometimes would spend a year on a record, recording an infinite number of takes with musicians he worked with for years and years.

Anyway, today we can read Landau’s review of an album that has certainly stood the test of time.

Bob Dylan, Blood On The Tracks

Reviewed by Jon Landau (for Rolling Stone)

Bob Dylan may be the Charlie Chaplin of rock & roll. Both men are regarded as geniuses by their entire audience. Both were proclaimed revolutionaries for their early work and subjected to exhaustive attack when later works were thought to be inferior. Both developed their art without so much as a nodding glance toward their peers. Both are multitalented: Chaplin as a director, actor, writer and musician; Dylan as a recording artist, singer, songwriter, prose writer and poet. Both superimposed their personalities over the techniques of their art forms. They rejected the peculiarly 20th century notion that confuses the advancement of the techniques and mechanics of an art form with the growth of art itself. They have stood alone.

When Charlie Chaplin was criticized, it was for his direction, especially in the seemingly lethargic later movies. When I criticize Dylan now, it’s not for his abilities as a singer or songwriter, which are extraordinary, but for his shortcomings as a record maker. Part of me believes that the completed record is the final measure of a pop musician’s accomplishment, just as the completed film is the final measure of a film artist’s accomplishments. It doesn’t matter how an artist gets there — Robert Johnson, Woody Guthrie (and Dylan himself upon occasion) did it with just a voice, a song and a guitar, while Phil Spector did it with orchestras, studios and borrowed voices. But I don’t believe that by the normal criteria for judging records — the mixture of sound playing, singing and words — that Dylan has gotten there often enough or consistently enough.

Chaplin transcended his lack of interest in the function of directing through his physical presence. Almost everyone recognizes that his face was the equal of other directors’ cameras, that his acting became his direction. But Dylan has no one trait — not even his lyrics — that is the equal of Chaplin’s acting. In this respect, Elvis Presley may be more representative of a rock artist whose raw talent has overcome a lack of interest and control in the process of making records.

Read the rest of this review here.

Bob Dylan – Tangled Up In Blue (New York Version 1974 Stereo)

Bob Dylan – You’re A Big Girl Now (New York Version)

Bob Dylan – Idiot Wind (New York Version 1974 Stereo)

Bob Dylan – Lily, Rosemary & The Jack Of Hearts (New York Version Stereo 1974)

Bob Dylan – If You See Her, Say Hello (New York Version 1974 Stereo)

-– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –-

—

[I published my novel, True Love Scars, in August of 2014.” Rolling Stone has a great review of my book. Read it here. And Doom & Gloom From The Tomb ran this review which I dig. There’s info about True Love Scars here.]

Fifty-three years ago, on March 11, 1962, Cynthia Gooding’s Folksinger’s Choice radio show featuring Bob Dylan aired on WBAI in New York.

This was Dylan’s first radio interview. His debut album, Bob Dylan, recorded in November 1961, would not be released for another week.

If you haven’t yet heard these performances, now is the time! And if you have, another listen is in order.

I’ve included a transcript of the show below the YouTube clips.

Enjoy!

1 “(I heard That) Lonesome Whistle Blow” (after the song ends if you go to about the seven minute point you can hear some of the interview):

2 “Fixin’ To Die”:

3 “Smokestack Lightning”:

4 “Hard Travellin'”:

5 “The Death Of Emmett Till”:

6 “Standing On The Highway”:

7 “Roll On, John”:

8 “Stealin'”:

9 “It Makes A Long Time Man Feel Bad”:

10 “Baby Please Don’t Go”:

11 “Hard Times In New York”:

Here’s a transcript of the show:

CG: That was Bob Dylan. Just one man doing all that. Playing the … er … mouth harp and guitar because, well, when you do this you have to wear a little sort of, what another person might call a necklace.

BD: Yeah !

CG: And then it’s got joints so that you can bring the mouth harp up to where you can reach it. To play it. Bob Dylan is, well, you must be twenty years old now aren’t you?

BD: Yeah. I must be twenty. (laughs)

CG: (laughs) Are you?

BD: Yeah. I’m twenty, I’m twenty.

CG: When I first heard Bob Dylan it was, I think, about three years ago in Minneapolis, and at that time you were thinking of being a rock and roll singer weren’t you?

BD: Well at that time I was just sort of doin’ nothin’. I was there.

CG: Well, you were studying.

BD: I was working, I guess. l was making pretend I was going to school out there. I’d just come there from south Dakota. That was about three years ago?

CG: Yeah.?

BD: Yeah, I’d come there from Sioux Falls. That was only about the place you didn’t have to go too far to find the Mississippi River. It runs right through the town you know. (laughs).

CG: You’ve been singing … you’ve sung now at Gerdes here in town and have you sung at any of the coffee houses?

BD: Yeah, I’ve sung at the Gaslight. That was a long time ago though. I used to play down in the Wha too. You ever know where that place is?

CG: Yeah, I didn’t know you sung there though.

BD: Yeah, I sung down there during the afternoons. I played my harmonica for this guy there who was singing. He used to give me a dollar to play every day with him, from 2 o’clock in the afternoon until 8.30 at night. He gave me a dollar plus a cheese burger.

CG: Wow, a thin one or a thick one?

BD: I couldn’t much tell in those days.

CG: Well, whatever got you off rock ‘n roll and on to folk music?

BD: Well, I never really got onto this, they were just sort of, I dunno, I wasn’t calling it anything then you know, I wasn’t really singing rock ‘n roll, I was singing Muddy Waters songs and I was writing songs, and I was singing Woody Guthrie songs and also I sung Hank Williams songs and Johnny Cash, I think.

CG: Yeah, I think the ones that I heard were a couple of the Johnny Cash songs.

BD: Yeah, this one I just sang for you is Hank Williams.

CG: It’s a nice song too.

BD: Lonesome Whistle.

CG: Heartbreaking.

BD: Yeah.

CG: And you’ve been writing songs as long as you’ve been singing.

BD: Well no, Yeah. Actually, I guess you could say that. Are these, ah, these are French ones, yeah?

CG: No, they are healthy cigarettes. They’re healthy because they’ve got a long filter and no tobacco.

BD: That’s the kind I need.

CG: And now you’re doing a record for Columbia?

BD: Yeah, I made it already. It’s coming out next month. Or not next month, yeah, it’s coming out in March.

CG: And what’s it going to be called?

BD: Ah, Bob Dylan, I think.

CG: That’s a novel title for a record.

BD: Yeah, it’s really strange.

CG: Yeah and hmm this is one of the quickest rises in folk music wouldn’t you say?

BD: Yeah, but I really don’t think to myself as, a you know, a folk singer, er folk singer thing, er, because I don’t really much play across the country, in any of these places, you know? I’m not on a circuit or anything like that like those other folk singers so ah, I play once in a while you know. But I dunno’ I like more than just folk music too and I sing more than just folk music. I mean as such, a lot of people they’re just folk music, folk music, folk music you know. I like folk music like Hobart Smith stuff an all that but I don’t sing much of that and when I do it’s probably a modified version of something. Not a modified version, I don’t know how to explain it. It’s just there’s more to it, I think. Old time jazz things you know. Jelly Roll Morton, you know, stuff like that.

CG: Well, what I would like is for you to sing some songs, you know, from different parts of your short history. Short because you’re only 20 now.

BD: Yeah, OK. Let’s see. I’m looking for one.

CG: He has the, I gather, a small part of his repertoire, pasted to his guitar.

BD: Yeah. Well, this is you know actually, I don’t even know some of these songs, this list I put on ‘cos other people got it on, you know, and I copied the best songs I could find down here from all these guitar players list. So I don’t know a lot of these, you know. It gives me something to do though on stage.

CG: Yeah, like something to look at.

BD: Yeah. I’ll sing you, oh, you wanna hear a blues song?

CG: Sure.

BD: This one’s called Fixin’ To Die.

Track 2: Fixin’ To Die

CG: That’s a great song. How much of it is yours?

BD: That’s ah, I don’t know. I can’t remember. My hands are cold; it’s a pretty cold studio.

CG: It s the coldest studio !

BD: Usually can do this (picking a few notes). There, I just wanted to do it once.

CG: You’re a very good friend of John Lee Hookers, aren’t you?

BD: Yeah, I’m a friend of his.

CG: Do you sing any of his songs at all?

BD: Well, no I don’t sing any of his really. I sing one of Howlin’ Wolfs. You wanna hear that one again?

CG: Well, first I wanna ask you, um, why you don’t sing any of his because I know you like them.

BD: I play harmonica with him, and I sing with him. But I don’t do, sing, any of his songs because, I might sing a version of one of them, but I don’t sing any like he does, ‘cos I don’t think anybody sings any of his songs to tell you the truth. He’s a funny guy to sing like.

CG: Hard guy to sing like too.

BD: This is, I’ll see if I can find a key here and do this one. I heard this one a long time ago. This is one, I never do it.

CG: This is the Howlin’ Wolf song

BD: Yeah.

Track 3: Smokestack Lightning

BD: You like that?

CG: Yeah, I sure do. You’re very brave to try and sing that kind of a howling song.

BD: Yeah, it’s Howlin’ Wolf.

CG: Yeah. Another of the singers that you’re a very good friend of is, I know, Woody Guthrie.

BD: Yeah.

CG: Did you, you said er singing his songs, or rather his songs were some of the first ones that you sang.

BD: Yeah.

CG: Which ones did you sing of his?

BD: Well, I sing…

CG: Or which do you like the best perhaps I should say.

BD: Well, which ones you’re gonna hear. Here, I’ll sing you one, if I get it together here.

CG: In order for Bob to put on his necklace which is what he holds up the mouth harp with, he’s gotta take his hat off. Then he puts on the necklace. Then he puts the hat back on.

BD: Yeah.

CG: Then he screws up the necklace so he can put the mouth harp in it. It’s a complicated business.

BD: You know, the necklace gotta go round the collar.

CG: Also, in case any of you don’t know, in order for Bob to decide what key he’s gonna sing in, he gotta, well, first, he decides what key he s gonna sing in and then he’s gotta find the mouth harp that’s in that key. And, then he’s gotta put the mouth harp in the necklace.

BD: Yeah. I’ll sing you Hard Travellin’. How’s that one? Everybody sings it, but he likes that one.

Track 4: Hard Travellin’

CG: Nice, you started off slow but boy you ended up.

BD: Yeah, that’s a thing of mine there.

CG: Tell me about the songs that you’ve sung, that you’ve written yourself that you sing.

BD: Oh those are … I don’t claim to call them folk songs or anything. I just call them contemporary songs, I guess. You know, there’s a lot of people paint, you know. If they’ve got something that they wanna say, you know, they paint. Or other people write. Well, I just, you know write a song it’s the same thing . You wanna hear one?

CG: Why, yes. That’s just what I had in mind Bob Dylan. Whatever made you think of that.

BD: Well, let me see. What kind do you wanna hear? I got a new one I wrote.

CG: Yeah. you said you were gonna play some of your new ones for me.

BD: Yeah, I got a new one, er. This one’s called, em, Emmett Till. Oh, by the way, the melody here is, excuse me, the melody’s, I stole the melody from Len Chandler. An’ he’s a funny guy. He’s a, he’s a folk singer guy. He uses a lot of funny chords you know when he plays and he’s always getting to, want me, to use some of these chords, you know, trying to teach me new chords all the time. Well, he played me this one. Said don’t those chords sound nice? An’ I said they sure do, an so I stole it, stole the whole thing.

CG: That was his first mistake.

BD: Yeah … Naughty tips.

Track 5: Emmett Till

BD: You like that one?

CG: It’s one of the greatest contemporary ballads I’ve ever heard. It s tremendous.

BD: You think so?

CG: Oh yes !

BD: Thanks !

CG: It’s got some lines that are just make you stop breathing, great. Have you sung that for Woody Guthrie?

BD: No. I’m gonna sing that for him next time.

CG: Gonna sing that one for him?

BD: Yeah.

CG: Oh Yeah.

BD: I just wrote that one about last week, I think.

CG: Pine song. It makes me very proud. It’s uh, what’s so magnificent about it to me, is that it doesn’t have any sense of being written, you know. It sounds as if it just came out of …. it doesn’t have any of those little poetic contortions that mess up so many contemporary ballads, you know.

BD: Oh yeah, I try to keep it working.

CG: Yeah, and you sing it so straight. That’s fine.

BD: Just wait til’ Len Chandler hears the melody though.

CG: He’ll probably be very pleased with what you did to it. What song does he sing to it?

BD: He sings another one he wrote, you know. About some bus driver out in Colorado, that crashed a school bus with 27 kids. That’s a good one too. It’s a good song.

CG: What other songs are you gonna sing?

BD: You wanna hear another one?

CG: I wanna hear tons more.

BD: OK, I’ll sing ya, I never get a chance to sing a lot of, let me sing you just a plain ordinary one.

CG: Fine.

BD: I’ll tune this one. It’s open E. Oh ! I got one, I got two of ’em. I broke my fingernail so it might not be so, it might slip a few times.

Track 6: Standing On The Highway

BD: You like that?

CG: Yes I do. You know the eight of diamonds is delay, and the ace of spades is death so that sort of goes in with the two roads, doesn’t it?

BD: I learned that from the carnival.

CG: From who?

BD: Carnival, I used to travel with the carnival. I used to speak of those things all the time.

CG: Oh. You can read cards too?

BD: Humm, I can’t read cards. I really believe in palm reading, but for a bunch of personal things, I don’t, personal experiences, I don’t believe too much in the cards. I like to think I don’t believe too much in the cards, anyhow.

CG: So you go out of your way not to get em read, so you won’t believe them. How long were you with the carnival?

BD: I was with the carnival off and on for about six years.

CG: What were you doing?

BD: Oh, just about everything. Uh, I was clean-up boy, I used to be on the main line, on the ferris wheel, uh, do just run rides. I used to do all kinds of stuff like that.

CG: Didn’t that interfere with your schooling?

BD: Well, I skipped a bunch of things, and I didn’t go to school a bunch of years and I skipped this and I skipped that.

CG: That’s what I figured.

BD: All came out even though.

CG: What, you were gonna … you were gonna, sing another blues, you said.

BD: Oh yeah, I’ll sing you this one. This is a nice slow one. I learned this … you know Ralph Rensler?

CG: Sure.

BD: I learned this sort of thing from him. A version of this, I got the idea from him. This isn’t the blues, but, how much time we got?

CG: Oh, we got half an hour.

BD: Oh, good.

Track 7: Roll On John

CG: That’s a lonesome accompaniment too. Oh my !

BD: You like that one?

CG: It makes you feel even lonelier. How much of that last one was yours by the way?

BD: Well, I dunno, maybe one or two verses.

CG: Where’d the rest of it come from?

BD: Well, like I say, I got the idea for Roll On John from Ralph Rensler.

CG: Oh! I see.

BD: And then I got … the rest just sort of fell together. Here’s one, I’ll bet you’ll remember. Yay, I bet you’ll know this one.

CG: Take the hat off, put on the necklace, put the hat back on. Nobody’s ever seen Bob Dylan without his hat excepting when he’s putting on his necklace. Is there … is there a more dignified name for that thing?

BD: What, the, this?

CG: Yeah the brace, what’s it called?

BD: Er, harmonica holder.

CG: Oh, I think necklace is better than that.

BD: Yeah, ha ha. This one here’s an old jug band song.

Track 8: Stealin’

BD: Like that? That’s called Stealin’.

CG: I figured. You haven’t been playing the harrnonica too long, have you?

BD: Oh yeah, oh yeah, yeah, yeah. I been playing the harmonica for a long time. I just have never had … couldn’t play ’em at the same time. I used to play the smaller Hohners. I never knew harmonica holders existed, the real kind like this. I used to go ahead and play with the coat hanger. That never really held out so good. I used to put tape around it, you know, and then it would hold out pretty good. But then there were smaller harmonicas than these, you know, they’re about this far an’ I used to put them in my mouth. But I, but I got bad teeth, you know, and some kind of thing back there you know. Maybe there’s … I don’t know what it was, a filling or something. I don’t know what it was in there but it used to magnify.

CG: Oh yes.

BD: Not magnified but magnet, you know. Man, this whole harmonica would go, you know, wham, drop from my mouth like that. So I couldn’t hold it onto my teeth very much.

CG: Yeah, it’s like, sometimes you get a piece of tin foil in your mouth and it goes wow. It’s terrible. But let’s not talk about that.

BD: No, I don’t want to talk about that either.

CG: At the carnival did you learn songs?

BD: No, I learned how to sing though. That’s more important.

CG: Yeah. You made up the songs even then.

BD: Er, actually, I wrote a song once. I’m trying to find, a real good song I wrote. An’ it’s about this lady I knew in the carnival. An’ er, they had a side show, I only, I was, this was, Thomas show, Roy B Thomas shows, and there was, they had a freak show in it, you know, and all the midgets and all that kind of stuff. An’ there was one lady in there really bad shape. Like her skin had been all burned when she was a little baby, you know, and it didn’t grow right, and so she was like a freak. An’ all these people would pay money, you know, to come and see and … er … that really sort of got to me, you know. They’d come and see, and I mean, she was very, she didn’t really look like normal, she had this funny kind of skin and they passed her of as the elephant lady. And, er, like she was just burned completely since she was a little baby, er.

And … er, it’s a funny thing about them: I know how these people think, you know. Like when they wanna sell you stuff, you know, the spectators. And I don’t see why people don’t buy something, because, you know, like they sell little cards of themselves for, you know, like ten cents, you know. They got a picture on it and it’s got some story, you know. And they’ve very funny thinking, like they get up there like, a lot of them are very smart, you know, because they’ve had to do this, I mean, still you can’t. A lot of them are great people, you know. But like, they got a funny thing in their minds. Like they want to. Here they are on the stage, they wanna make you have two thoughts. Like, they wanna make you think that, er, they don’t feel, er, bad about themselves. They want you to think that they just go on living everyday and they don’t ever think about their, what’s bothering them, they don’t ever think about their condition. An’ also they wanna make you feel sorry for them, an’ they gotta do that two ways you see And er … they do it, a lot of them do it. And … er, it’s er. I had a good friend, this woman who was like that, and I wrote a song for her, you know, a long time ago. An’ lost it some place. It’s just about, just speakin’ from first person, like here I am, you know, and sort a like, talkin’ to you, and trying, an’ it was called, “Won’t You Buy A Postcard”. That’s the name of the song I wrote. Can’t remember that one though.

CG: There’s a lot of circus literature about how freaks don’t mind being freaks but it’s very hard to believe.

BD: Oh yeah.

CG: You’re absolutely right, that they would have to look at it two ways at the same time. Did you manage to get both ways into the song?

BD: Yeah. I lost the song.

CG: I hope you fond it and when you find it sing it for me.

BD: I got a verse here of some… You know Ian and Silvia?

CG: Oh sure. Ian and Silvia are at the Bitter End Club.

BD: I sort of borrowed this from them.

CG: He’s looking for a harmonica.

BD: I don’t have to take the necklace off; necklace as you call it. You might have heard them do it. This is the same song. I used to do this one.

Track 9: Makes A Long Time Man Feel Bad

BD: Got sort of… You like that one?

CG: Boy it, when you…

BD: That’s got them funny chords in it.

CG: …really get going there’s a tremendous sort of push that you give things that’s wild.

BD: Oh, you really think so?

CG: No, I was just talking.

BD: I’ll take off my necklace.

CG: Without taking off your hat.

BD: No.

CG: Well, then the thing is you see that …

BD: I’m getting good at this.

CG: Yah. After he takes off the necklace or puts it on he’s gotta fluff up the hat again every time.

BD: Yeah. I got it cleaned and blocked last week.

CG: What did you wear on your head? (laughing)

BD: Stetson. You seen me wear that Stetson.

CG: Oh yeah, you were wearing somebody’s Stetson.

BD: It was mine. I got that for a present.

CG: So why don’t you wear it? ‘Cause you like this one better?

BD: I like this one better. It’s been with me longer.

CG: What happens when you take it off for any length of time? You go to sleep?

BD: Yeah.

CG: I see.

BD: Or else I’m in the bathroom or somethin’. Well actually just when I go to sleep. I wanted to sing Baby Please Don ‘t Go because I’ve wanted to hear how that sounded.

Track 10; Baby Please Don’t Go

CG: That’s a nice song too. You said that you’ve written several new songs lately.

BD: Yeah.

CG: You’ve only sung one of them. You realise that? I know I’m working you very hard for this hour of the morning, but there it is.

BD: Yeah, this really isn’t a new one but this is one of the ones. You’ll like it. I wrote this one before I got this Columbia Records thing. Just about when I got it, you know. I like New York, but this is a song from one person’s angle.

Track 11: Hard Times In New York Town

CG: That’s a very nice song, Bob Dylan. You’ve been listening to Bob Dylan playing some, playing and singing some of his songs and some of the songs that he’s learned from other people. And thank you very, very much for coming down here and working so hard.

BD: It’s my pleasure to come down.

CG: When you’re rich and famous are you gonna wear the hat too?

BD: Oh, I’m never gonna become rich and famous.

CG: And you’re never gonna take off the hat either.

BD: No.

CG: And this has been Folksingers Choice and I’m Cynthia Gooding. I’ll be here next week at the same time.

Transcript via Expecting Rain. Thanks!!!

-– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –-

—

[I published my novel, True Love Scars, in August of 2014.” Rolling Stone has a great review of my book. Read it here. And Doom & Gloom From The Tomb ran this review which I dig. There’s info about True Love Scars here.]

Here are nine things I learned from Bob Dylan’s AARP interview.

1) Bob Dylan listened to tons of big band music as a kid:

“Early on, before rock ‘n’ roll, I listened to big band music: Harry James, Russ Columbo, Glenn Miller. Singers like Jo Stafford, Kay Starr, Dick Haymes. Anything that came over the radio and music played by bands in hotels that our parents could dance to. We had a big radio that looked like a jukebox, with a record player on the top.”

2) Bob Dylan thinks the access to most of recorded music that the Internet now makes possible is a negative:

“Well, if you’re just a member of the general public, and you have all this music available to you, what do you listen to? How many of these things are you going to listen to at the same time? Your head is just going to get jammed — it’s all going to become a blur, I would think. Back in the day, if you wanted to hear Memphis Minnie, you had to seek a compilation record, which would have a Memphis Minnie song on it. And if you heard Memphis Minnie back then, you would just accidentally discover her on a record that also had Son House and Skip James and the Memphis Jug Band. And then maybe you’d seek Memphis Minnie in some other places — a song here, a song there. You’d try to find out who she was. Is she still alive? Does she play? Can she teach me anything? Can I hang out with her? Can I do anything for her? Does she need anything? But now, if you want to hear Memphis Minnie, you can go hear a thousand songs. Likewise, all the rest of those performers, like Blind Lemon [Jefferson]. In the old days, maybe you’d hear “Matchbox” and “Prison Cell Blues.” That would be all you would hear, so those songs would be prominent in your mind. But when you hear an onslaught of 100 more songs of Blind Lemon, then it’s like, “Oh man! This is overkill!” It’s so easy you might appreciate it a lot less.”

3) Bob Dylan is such a fan of Picasso he’d like to be him – maybe:

“Well, I might trade places with Picasso if I could, creatively speaking. I’d like to think I was the boss of my creative process, too, and I could just do anything I wanted whenever I wanted and it would all be on a grand scale. But of course, that’s not true. Like Sinatra, there was only one Picasso.”

4) Bob Dylan’s take on creativity:

“[Creativity is] uncontrollable. It makes no sense in literal terms. I wish I could enlighten you, but I can’t — just sound stupid trying. But I’ll try. It starts like this. What kind of song do I need to play in my show? What don’t I have? It always starts with what I don’t have instead of doing more of the same. I need all kinds of songs — fast ones, slow ones, minor key, ballads, rumbas — and they all get juggled around during a live show. I’ve been trying for years to come up with songs that have the feeling of a Shakespearean drama, so I’m always starting with that. Once I can focus in on something, I just play it in my mind until an idea comes from out of nowhere, and it’s usually the key to the whole song. It’s the idea that matters. The idea is floating around long before me. It’s like electricity was around long before Edison harnessed it. Communism was around before Lenin took over. Pete Townshend thought about Tommy for years before he actually wrote any songs for it. So creativity has a lot to do with the main idea. Inspiration is what comes when you are dealing with the idea. But inspiration won’t invite what’s not there to begin with.”

5) Bob Dylan believes “self-sufficiency creates happiness”:

“OK, a lot of people say there is no happiness in this life, and certainly there’s no permanent happiness. But self-sufficiency creates happiness. Happiness is a state of bliss. Actually, it never crosses my mind. Just because you’re satisfied one moment — saying yes, it’s a good meal, makes me happy — well, that’s not going to necessarily be true the next hour. Life has its ups and downs, and time has to be your partner, you know? Really, time is your soul mate. Children are happy. But they haven’t really experienced ups and downs yet. I’m not exactly sure what happiness even means, to tell you the truth. I don’t know if I personally could define it. [Happiness is] like water — it slips through your hands. As long as there’s suffering, you can only be so happy. How can a person be happy if he has misfortune? Does money make a person happy? Some wealthy billionaire who can buy 30 cars and maybe buy a sports team, is that guy happy? What then would make him happier? Does it make him happy giving his money away to foreign countries? Is there more contentment in that than giving it here to the inner cities and creating jobs? Nowhere does it say that one of the government’s responsibilities is to create jobs. That is a false premise. But if you like lies, go ahead and believe it. The government’s not going to create jobs. It doesn’t have to. People have to create jobs, and these big billionaires are the ones who can do it. We don’t see that happening. We see crime and inner cities exploding, with people who have nothing to do but meander around, turning to drink and drugs, into killers and jailbirds. They could all have work created for them by all these hotshot billionaires. For sure, that would create a lot of happiness. Now, I’m not saying they have to — I’m not talking about communism — but what do they do with their money? Do they use it in virtuous ways? If you have no idea what virtue is all about, look it up in a Greek dictionary. There’s nothing namby-pamby about it.

6) Bob Dylan thinks Billy Graham, the evangelist, was “like rock ’n’ roll personified”:

When I was growing up, Billy Graham was very popular. He was the greatest preacher and evangelist of my time — that guy could save souls and did. I went to two or three of his rallies in the ’50s or ’60s. This guy was like rock ’n’ roll personified — volatile, explosive. He had the hair, the tone, the elocution — when he spoke, he brought the storm down. Clouds parted. Souls got saved, sometimes 30- or 40,000 of them. If you ever went to a Billy Graham rally back then, you were changed forever. There’s never been a preacher like him. He could fill football stadiums before anybody. He could fill Giants Stadium more than even the Giants football team. Seems like a long time ago. Long before Mick Jagger sang his first note or Bruce strapped on his first guitar — that’s some of the part of rock ’n’ roll that I retained. I had to. I saw Billy Graham in the flesh and heard him loud and clear.

7) These days Bob Dylan can relate more to a song like “I’m A Fool To Want You” than to his own “Queen Jane Approximately”:

“These songs [on Shadows In The Night] have been written by people who went out of fashion years ago. I’m probably someone who helped put them out of fashion. But what they did is a lost art form. Just like da Vinci and Renoir and van Gogh. Nobody paints like that anymore either. But it can’t be wrong to try. So a song like “I’m a Fool to Want You” — I know that song. I can sing that song. I’ve felt every word in that song. I mean, I know that song. It’s like I wrote it. It’s easier for me to sing that song than it is to sing, “Won’t you come see me, Queen Jane.” At one time that wouldn’t have been so. But now it is. Because “Queen Jane” might be a little bit outdated. It can’t be outrun. But this song is not outdated. It has to do with human emotion, which is a constant thing. There’s nothing contrived in these songs. There’s not one false word in any of them. They’re eternal, lyrically and musically.”

8) Bob Dylan clearly understands what recording an album of standards, Shadows in The Night, means — that in a way he is making peace with a music that, as he puts it, “rock ’n’ roll came to destroy”:

“To those of us who grew up with these kinds of songs and didn’t think much of it, these are the same songs that rock ’n’ roll came to destroy — music hall, tangos, pop songs from the ’40s, fox-trots, rumbas, Irving Berlin, Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Hammerstein. Composers of great renown.”

9) Dylan is asked if Frank Sinatra was “too square to admit liking” back in the late ’50s/’60s:

“Square? I don’t think anybody would have been bold enough to call Frank Sinatra square. Kerouac listened to him, along with Bird [Charlie Parker] and Dizzy [Gillespie]. But I myself never bought any Frank Sinatra records back then, if that’s what you mean. I never listened to Frank as an influence. All I had to go on were records, and they were all over the place, orchestrated in one way or another. Swing music, Count Basie, romantic ballads, jazz bands — it was hard to get a fix on him. But like I say, you’d hear him anyway. You’d hear him in a car or a jukebox. You were conscious of Frank Sinatra no matter what age you were. Certainly nobody worshipped Frank Sinatra in the ’60s like they did in the ’40s. But he never went away. All those other things that we thought were here to stay, they did go away. But he never did.”

Frank Sinatra, “Ebb Tide”:

-– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –-

—

[I published my novel, True Love Scars, in August of 2014.” Rolling Stone has a great review of my book. Read it here. And Doom & Gloom From The Tomb ran this review which I dig. There’s info about True Love Scars here.]

If you’ve even seen the great Film Noir classics “Double Indemnity,” “Detour” or Orson Welles “Touch Of Evil,” than you know what Bob Dylan is up to in his new video for the song “The Night We Called It A Day” off his latest album, Shadows In The Night.

The black and white video finds characters played by Dylan, Tracy Phillips and Nash Edgerton involved in some kind of double double cross that involves a diamond ring and a double murder.

Check it out:

And if you haven’t already, read my column about Shadows In The Night.

-– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –-

—

[I published my novel, True Love Scars, in August of 2014.” Rolling Stone has a great review of my book. Read it here. And Doom & Gloom From The Tomb ran this review which I dig. There’s info about True Love Scars here.]

I always dug Jerry Garcia’s voice and I think it’s perfect for delivering this song. Intuitively Garcia got this song, and you hear it.

Some great guitar playing on some of these versions too.

Here’s a studio recording of “Visions of Johanna” by Garcia.

Here’s the Grateful Dead doing “Visions of Johanna” live, The Spectrum, March 18, 1995, Philadelphia, PA:

And a version from the Dead at Hampton Coliseum, March 19, 1986, Hampton, VA:

Today I have part two of this amazing interview from February 1966 that Bob Dylan did for Playboy magazine.

I posted part one yesterday.

Nat Hentoff, who had profiled Dylan for the New Yorker in 1964, is the interviewer.

Dylan says some fascinating things, especially given that we now know what’s happened since 1966. This interview was done after the release of Highway 61 Revisited but before Blonde On Blonde was released.

Just one example:

“I refuse to be any kind of Lawrence Welk or something like that. I’ll continue making the records. They’re not going to be any better from now on, they’re gonna be just different.”

-– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –-

—

[I published my novel, True Love Scars, in August of 2014.” Rolling Stone has a great review of my book. Read it here. And Doom & Gloom From The Tomb ran this review which I dig. There’s info about True Love Scars here.]