Last night Phil Lesh & Terrapin Family Band performed in San Rafael, Ca at Terrapin Crossroads and played Neil Young’s “Ohio.”

Check it out:

-– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –

Last night Phil Lesh & Terrapin Family Band performed in San Rafael, Ca at Terrapin Crossroads and played Neil Young’s “Ohio.”

Check it out:

-– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –

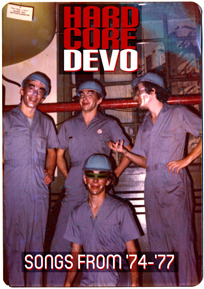

Devo Redux: Devo will perform its experimental music from 1974-1977 on a North American tour this summer. The 10-date North American tour is dedicated to the memory of the late Robert “Bob 2″ Casale, whose family will get a portion of the proceeds. According to Bob 2’s brother Gerald, Gerald Casale, Bob 2 “had no will or insurance.” — Slicing Up Eyeballs

Dylan’s Bed Jumping: Bob Dylan jumped on Johnny Cash’s bed the first time they met, according to the account the singer gave to his son, John Carter Cash which he commented about in a Reddit Q&A. Johnny Cash met Dylan in a New York City hotel room in the early Sixties. Although they had exchanged letters, upon finally meeting one another, “Dylan rushed into his room, jumped on the bed and began bouncing up and down chanting, ‘I met Johnny Cash, I met Johnny Cash.'” Although they fell out of touch as time went by, they remained friends. — Rolling Stone

Break the Code?: Fans think they’ve discovered the release date for ç upcoming album in a teaser video released this week. The date? May 26, 2014. Time will tell. — NME

Check out the video for yourself:

Gimme Money!: Neil Young’s PonoMusic Kickstarter campaign has now passed the $5 million mark. As of Saturday, March 29, 2014 14,808 people had contributed $5,006,618.

A Love Supreme: Six rolls of undeveloped film shot by Chuck Stewart during sessions for John Coltrane’s transcendent album, A Love Supreme, were found by his son. Check out a few of the photos at the NPR website. — NPR

-– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post: sounds, visuals and/or news –

Neil Young’s PonoMusic campaign has now passed the five million mark.

As of today around noon, 14,808 people had contributed $5,006,618.

However many are not convinced PonoMusic is a hit.

The San Jose Mercury News ran this column by Troy Wolverton:

I hate to be the one to break it to rock ’n’ roll legend Neil Young, but his new digital music venture has about as much chance of succeeding as I have of winning a Grammy — maybe less.

Earlier this month at the South by Southwest music festival in Austin, Texas, Young unveiled Pono, a company that will offer a digital music player, an online store and music-management software all designed to work together, much like the iPod and iTunes. What makes Pono different is that it is focused on delivering a better audio experience.

The company will sell songs and albums in a high-resolution format that its player is designed for. According to Young, Pono will take listeners back to the recording studio and allow them to hear music in exactly the way the artists intended it to sound.

The company has already drawn a huge amount of buzz, and endorsements from artists and industry executives ranging from Sarah McLachlan to Warner Bros. Records Chairman Rob Cavallo. Meanwhile, a Kickstarter campaign the company is using to get its service off the ground topped its $800,00 fundraising goal within a day of Young’s announcement and had exceeded $2.6 million by the end of the week.

Yet, despite the enthusiasm surrounding it, Pono is an anachronistic and ill-considered solution to an all-but-nonexistent problem.

The service is modeled on how people used to listen to music five or 10 years ago, not how they listen today.

By and large, consumers are replacing stand-alone digital music players like the iPod with smartphones. And instead of plugging those players into their computers to sync their music, they’re getting music on their smartphones wirelessly…

Read the rest here.

– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post –

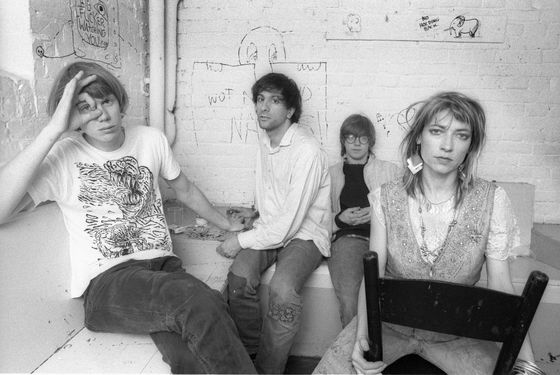

Cool interview with Thurston Moore over at Vulture magazine.

Jennifer Vineyard interviewed Moore. Here’s an excerpt:

I was born in 1958, and the Velvet Underground disbanded in the early ’70s, so I was aware of the Velvet Underground as a young kid. I remember finding the banana LP at Sears, because you’d buy records in places like department stores. It wasn’t until later I found a record store in New Haven, Connecticut, called Cutler’s, where we’d find records that were more obscure. You would see them written about every once in a while, either in Rolling Stone or CREEM or the magazines of the time, like Circus, Hit Parader, and Rock Scene. Rock Scene was the most important one because it was primarily events that were happening in New York City. They would have all the heavyweights in there, like Led Zeppelin and David Bowie, but they were also covering what was going on in the margins. That was really exciting, wondering what was going on in these little clubs in New York City, because the people just looked fabulous, and the music sounded more intriguing than what was going on at the time with youth culture, which was sort of a fallout from hippie and post-Vietnam kind of vibe. At that time, the hip thing was going back to the country, escaping the city and smoking pot with Joni Mitchell and David Crosby on the porch with the dogs. And there was all this music from Europe and England that had more pomp to it, like prog rock—Yes and Emerson, Lake and Palmer. So to me, seeing images of Patti Smith standing on the subway platform—all of a sudden it was like this new idea that it was kind of cool to be urban. And that was like our new definition of identity. I wanted to investigate that. The reality of it was the city was destitute, and it became this kind of postapocalyptic landscape for artists, and there’s something very enchanting in that. I ran to it. I wanted to see Patti Smith.

Connecticut was a great place to be, because the bands would come to you. But I was very curious about going to New York City, to Max’s Kansas City. So as soon as I could figure it out, I drove to New York City and sought out Max’s Kansas City. I knew it was on Park Avenue—which is a very long avenue, by the way! So I drove along Park Avenue, and I yelled out the window, “Where’s Max’s?” [Laughs.] I eventually found it at the very bottom of the avenue, right near Union Square.

Read the rest here.

Thurston Moore, “Detonation”:

Check out three songs by The Hold Steady live from WYNC’s Soundcheck.

“Spinners”:

“The Ambassador”:

“The Only Thing”:

– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post –

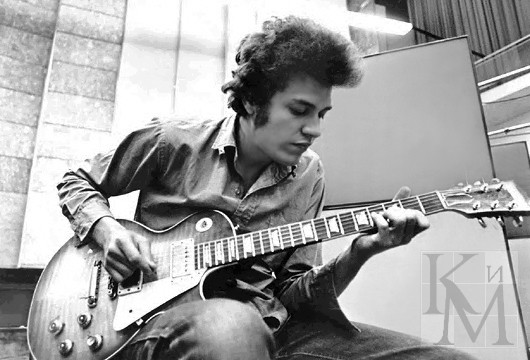

Michael Bloomfield played the electrifying lead guitar parts on Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited. He was there in the studio, an active participant, as Dylan and the other musicians Dylan had assembled created a radical new rock sound.

Larry “Ratso” Sloman interviewed Bloomfield by phone in late 1975, while in the midst of reporting on Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Review tour. Sloman ended up writing an excellent book about the tour, “On the Road with Bob Dylan.”

Yesterday I excerpted part of Sloman’s interview with Bloomfield. Today I’ve got more from the interview. This picks up right after Bloomfield has spoken about meeting and hanging out with Dylan for the first time in Chicago in the early ’60s.

Michael Bloomfield: The next time I saw him was at a party in Chicago and he was traveling with a bodyguard, a big fucking Arab, named Victor Maimudes, an Arab, and he was a bodyguard, that’s what he was. I didn’t know that then, what did I know? I hung with the [blacks], what did I know about him and his bodyguard, and he was trying to get pussy and, believe me, he got a lot of pussy, and we hung out at that party and we talked…

The next time, I get a phone call from him, would I want to play on a record with him and I said, “All right.” And I really didn’t know he was a famous guy, I really didn’t know, I was so into the black music scene and Am radio that I didn’t know this guy was famous.

And I went to Woodstock, and I didn’t even have a guitar case, I just had my Telecaster and Bob picked me up at the bus station and took me to this house where he lived, which wasn’t so much, and Sara was there I think, and she made very strange food, tuna fish salad with peanuts in it, toasted, and he taught me these songs, “Like a Rolling Stone,” and all those songs from that album and he said, “I don’t want you to play any of that B. B. King shit, none of that fucking blues, I want you to play something else,” so we fooled around and finally played something he liked, it was very weird, he was playing in weird keys which he always does, all on the black keys on the piano, then he took me over to this big mansion and there was this old guy walking around and I said, “Who’s that?” and Bob said, “That’s Albert,” and I said, “Who’s Albert?” and he said that he was his manager, and I didn’t recognize Albert even though I had met him many times before. He had short hair before and now he looked like Ben Franklin, he looked like cumulus nimbus. I didn’t know who he was and I asked Bob if he was a cool guy and Bob said, “Oh, yeah.”

We fucked around there for a few days and then we went to New York to cut the record and I started seeing that this guy Dylan was really a famous guy, I mean he was invited to all the Baby Jane Holzer parties, and all these people would be walking around with him, and the Ronettes would come up to him and Phil Spector would be talking to him and I noticed that he and Albert and Neuwirth had this game that they would play and it was the beginning of the character armor, I think, it was intense put-downs of almost every human being that existed but the very few people in their aura that they didn’t do this to. It was Bob, Albert, and Neuwirth, they had a whole way of talking, I used to be able to imitate it. David Blue is a very good imitator of it, as a matter of fact I don’t even think he knows he’s imitating it. It’s just like this very intense putdown.

And he was very heavy into drinking wine, to stay calm and loose I guess. We went to this Chinese restaurant and I started putting Bob down, playing the dozens with him and I did it all night long and he and Albert loved it, they were in hysterics because it wasn’t the kind of putting down that they did, it was the dozens, and I talked about his momma and his family and everything, and I had a great time.

Oh, and then I remember one time Bob wouldn’t eat and Albert took him to Ratner’s and bought him plates of sturgeon and like mushroom barley soup and he was taking the sturgeon and just piece by little clump putting it in his mouth and saying, ‘Eat, sturgeon, good,’ I couldn’t believe what I was seeing, it was so fucking far out.

And we cut the album and that was extremely weird because no one knew what they were doing there. They had this producer who was as useless as tits on a pig, he was referred to exclusively out of his presence as Dylan’s [n–ger], this big tall guy, a hillbilly, Johnson, he was a good old boy, no doubt about it. I mean there were chord charts for these songs but no one had any idea what the music was supposed to sound like, what direction it was, the nearest that anyone had an idea was [Al] Kooper and he was there as a guitar player, and as soon as I came in and started playing, he picked up the organ, he was a good organ player but it was weird for Bob. We were doing songs like “Desolation Row” three or four times, takes and takes of that, and that’s crazy, it’s a long song. I mean the guy had to sing these fifteen-minute songs over and over again, it was really nuts. And Sam Lay from Paul Butterfield was playing the drums, and the bassist was Russ Savakus, I think it was the first time he had ever played electric bass in his life, he had been a studio upright player for years and years, and it all sort of went around Dylan. I mean like he didn’t direct the music, he just sang the songs and played piano and guitar and it just sort of went on around him, though I do believe he had a lot to do with mixing the record. But the sound was a matter of pure chance, whatever sound there was on that record was chance, the producer did not tell the people what to play or have a sound in mind, nor did Bob, or if he did he told no one about it, he just didn’t have the words to articulate it, so that folk-rock sound, as precedent-setting as it might have been, I was there man, I’m telling you it was a result of Chuckle-fucking, of people stepping on each other’s dicks until it came out right.

“Tombstone Blues” with Michael Bloomfield, lead guitar:

– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post –

French disco-freak Cerrone delivers a remix of this terrific Haim track, “If I Could Change Your Mind.”

French disco-freak Cerrone delivers a remix of this terrific Haim track, “If I Could Change Your Mind.”

Still, I like the original better.

– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post –

On March 18, 2014 at at Harpa in Reykjavík, Iceland, a benefit concert, Let’s Protect the Park, was held featuring Bjork, Patti Smith, Lykke Li and others.

Over $300,000 was raised for Icelandic environmental organizations.

Darren Aronofsky’s “Noah,” which was filmed in Iceland, was screened that night.

Listen to over an hour of the concert, including a beautiful set by Patti Smith.

Plus a fan-shot video of all the artists performing the Beastie Boys’ “Sabotage.”

– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post –

In Larry “Ratso” Sloman’s terrific book, “On the Road with Bob Dylan,” he interviews Michael Bloomfield on the phone in 1975. Bloomfield, of course, famously played on Highway 61 Revisited and was in the band when Dylan went electric at Newport in 1965.

Bloomfield recounts how in preparation for recording Blood on the Tracks, Dylan came to Bloomfield’s house in 1974 to play him the songs. Dylan was thinking about having Bloomfield play on the album.

Michael Bloomfield: The last time was atrocious, atrocious. He came over and there was a whole lot of secrecy involved, there couldn’t be anybody in the house. I wanted to tape the songs so I could learn them so I wouldn’t fuck ‘em up at the sessions…”

Larry Sloman: What songs?

“The ones that came out later on Blood on the Tracks. Anyway, he saw the tape recorder and he had this horrible look on his face like I was trying to put out a bootleg album or something and my little kid, who is like fantastically interested in anyone who plays music, never came into the room where Dylan was the entire several hours he was in the house. He started playing the goddamn songs from Blood on the Tracks and I couldn’t play, I couldn’t follow them, a friend of mine had come to the house and I had to chase him from the house. I’m telling you, the guy [Dylan] intimidated me, I don’t know what it was, it was like he had character armor or something, he was like a wall, he had a wall around him and I couldn’t reach through it. I used to know him a long time ago. He was sort of a normal guy or not a normal guy but knowable, but that last time I couldn’t get the knowable part of him out of him, and to try to get that part out of him would have been ass-kissing, it would have been being a sycophant, and it just isn’t worth kissing his ass, as a matter of fact, I don’t think he would have liked that anyway. It was one of the worst social and musical experiences of my life.

Sloman: What was he like?

Bloomfield: There was this frozen guy there. It was very disconcerting. It leads you to think, if I hadn’t spent some time in the last ten or eleven years with Bob that were extremely pleasant, where I got the hippie intuition that this was a very, very special and, in some ways, an extremely warm and perceptive human being, I would now say that this dude is a stone prick. Time has left him to be a shit, but I don’t see him that much, two isolated incidents over a period of ten years.

Sloman: What do you see as the cause of that?

Bloomfield: Character armor. It’s to keep his sanity, to keep away the people who are always wanting something from him. But if a lot of people relate to you as their concept of you, not your concept of you, you’re gonna have to do something to keep those people from driving you crazy, but if that is so strong that you can’t realize who is trying to fuck with you and who just wants to get along with the business, if you can’t tell the difference, it’s very difficult.

Sloman: How did you relate to him in the early days?

Bloomfield: When I first saw him he was playing in a night club, I had heard his first album, and Grossman got Dylan to play in a club in Chicago called The Bear and I went down there to cut Bob, to take my guitar and cut him, burn him, and he was a great guy, I mean we spent all day talking and jamming and hanging out and he was an incredibly appealing human being and any instincts I may have had in doing that was immediately stopped , and I was just charmed by the man.

That night, I saw him perform and if I had been charmed by just meeting him, me and my old lady were just bowled over watching him perform. I don’t’ know what, it was like this Little Richard song, ‘I don’t know what ou got but it moves me,’ man, this can sang this song called ‘Redwing’ about a boys’ prison and some funny talking blues about a picnic and he was fucking fantastic, not that it was the greatest playing or singing in the world, I don’t know what he had, man, but I’m telling you I just loved it, I mean I could have watched it nonstop forever and ever…

Bloomfield goes on to talk about getting a call from Dylan and going up to Woodstock and Dylan teaching him all the songs for Highway 61 Revisited and then going to New York and recording them. And then Bloomfield talks about playing with Dylan at Newport.

Bloomfield: So after that we like drifted apart, what was there to drift apart, we weren’t that tight, but after that when I’d see him he was a changed guy, honest to God, Larry, he was. There was a time he was one of the most charming human beings I had ever met and I mean charming, not in like the sense of being very nice, but I mean someone who cold beguile you, man, with his personality. You just had to say, ‘Man, this little fucking guy’s got a bit of an angel in him,’ God touched him in a certain way. And he changed, like that guy was gone or it must not be gone, any man that has that many kids, he must be relating that way to his children, but I never related to him that way again.

Anytime that I would see him, I would see him consciously be that cruel, man, I didn’t’ understand that game they played, that constant insane sort of sadistic put-down game. Who’s king of the hill? Who’s on top? To me it seemed like much ado about nothing but to Dave Blue and Phil Ochs it was real serious. I don’t think Blue’s ever escaped that time, in some ways it seems like he’s still trying to prove himself to Bob. I know David’s one of Bob’s biggest champions. ..

I feel the cat’s Pavlovized, he’s Tofflerized, he’s future-shocked. It would take a huge amount of debriefing or something to get him back to normal again, to put that character armor down. But if he’s happy, who am I to say? I can’t judge if he’s happy, this might be his happiness.

“Like A Rolling Stone,” Michael Bloomfield on lead guitar:

Bob Dylan, Like a Rolling Stone (vinyl) from dispensable library on Vimeo.

– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post –

Check out this tripply track from Jamie xx of The xx, “Sleep Sound.”

– A Days of the Crazy-Wild blog post –